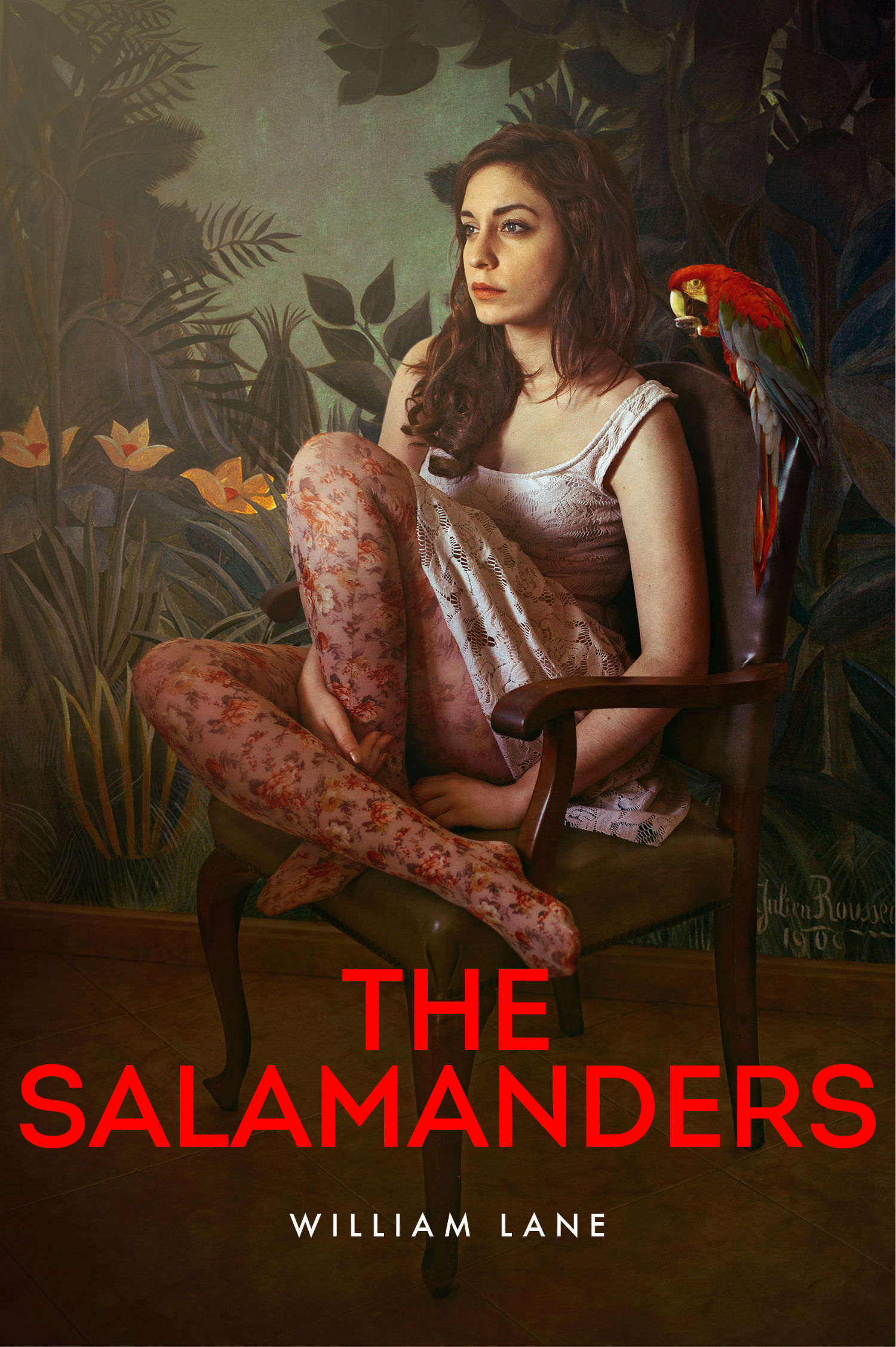

There is much for the Australian psyche to respond to in William Lane’s novel about memory and loss. The Salamanders begins in a holiday house straddling the beach and the bush where white cockatoos strip the timbers, taut blue-tongued lizards grip rock ledges, crickets stop singing abruptly and a nearby city is ringed by fire. The eyes of possums in the trees phosphoresce and in the morning the bellbirds call.

In this place, Lane distils the poetry of a time-honoured ritual: “Everyone arranged themselves in a circle about the [camp]fire and ate with their backs to the darkness. The ocean thumped between the distant silences.”

At the heart of this hallucinatory narrative is a painter called Peregrine, a monster of self-importance whose brush comes before his first wife, Ottilie, their three sons and an adopted daughter, and his second wife, Naomi (whom he has also divorced), and their two daughters.

A summer holiday sees them all, with the exception of Ottilie, who is some kind of spectre in the background, come together for a time of languid swimming, exploring and reading — and in Peregrine’s case, a frenzy of painting that no one is allowed to interfere with. Some couples arrive and leave in high dudgeon after Peregrine gives offence, others beg off visiting altogether.

Between painting bouts, Peregrine sleeps with both his ex-wife Naomi and one of their mutual friends, and at the end of the holiday he conveniently collapses as a result of alcohol consumption.

During this complicated holiday, what happens between Arthur, Peregrine’s son, and Rosie, the adopted daughter who is raised by Naomi, will mark the two children forever. They are not technically brother and sister, but the families regard them as such, and it is left to the reader to muse over whether their relations extended beyond childhood affections. We are also uncertain if something took place between Peregrine, with his penchant for painting nubile young girls, and Rosie, who affectionately fetched, carried and arranged his brushes.

The years pass, Arthur lives on his own in a little hut on the Hawkesbury River. Rosie, who is familiar with the front line of war zones, visits from London. Each retraces their earlier memories of a physically unforgettable place. There is a gentle erotic flare when Rosie says, “I’ve been dreaming of living in a place where one doesn’t need to wear clothes all the time.”

Water, not quite limpid, its colours and direction ever changing, becomes a metaphor for their exchanges. When Rosie smiles, Arthur’s insides “leapt like a fish”. Lane evokes the strangeness of their physical environment and the complexity of the living organisms all around them.

One of the first creatures Rosie sees is a salamander. “They’re actually skinks,’’ Arthur corrects her. “Salamanders, geckos, frill-necked lizards, water dragons … when I see a lizard I think of this country,” she replies. When Lane describes a place where the sandstone outcrops meet the river — “The stone staggered to the water ten thousand years at a time, under split-second eucalyptus downstrokes” — the reader is reminded of the antiquity of the land.

When Rosie’s restlessness sees them drive inland with little more than a backpack between them, a different kind of equally Australian adventure unfolds. They collect an English hitchhiker named Heath, who uncannily resembles Arthur and who describes Australia as “an unfenced paddock that covers a significant part of the globe”. Their journey sees Lane — based in NSW’s Hunter Valley — render the lean outback with the same poetic and hallucinatory prose that he uses to invoke the character of the coast and the Hawkesbury River.

They arrive at a mining town where the streets have names that suggest a “a kind of periodic table” (Carbon, Uranium, Fluoride). When they reach the realm of sunbaked carcasses and floodplains, locals take them hunting and exploring red caves for galleries of Aboriginal paintings of long-lost creatures. They arrive back on the coast and, quite abruptly, Rosie buys an open ticket. She “walked through the gate without looking back”.

Eventually she writes, with news that prompts to Arthur arrive in England, determined to see her, and to visit Peregrine, who has retreated to a small island off the mainland where he paints in bursts then lapses into a temporary catatonic state. He finds his father is serenely indifferent to the past.

The gentle rhythms of this book create a sensation of drifting on a tide and, indeed, Arthur and Rosie find themselves doing just that. Apart from the psychic damage parents can inflict on their children, this is also a memorable story about the strange Australian continent itself, with its sandstone escarpments, drowned river valleys fringed with mangroves, its desolate outback and its primeval creatures.

Patricia Anderson , The Australian, 24 September 2016