A plangent, lovely, melancholy treat, so special for its unexpectedness. Repetition, cadence, restraint, imagination: I was entranced and determined to read all his other work.

Kate Holden, The Australian 19 December 2015

Holland, an esteemed travel writer along the lines of Chatwin, has given us a work that explores home, exile and transience through the journey of a sixth-century monk. Navigating through oceans of Celtic and Christian mythology, we never discover if this purgatory is real or imagined until there’s a flash of the metafictive, with a man stranded in contemporary transit. It’s a typical stroke in an ambitious and surprising book from one of Australia’s most exciting writers.

Luke May, Readings Monthly November 2014

Yet Navigatio has a postmodern sense of the broader lives and interlinked fates of books. In one of the many lands they visit, the men find an old soldier; like one of Borges’s heroes, he has forgotten his own life, which has become a kind of dream. A little later, the same visit is repeated — along with hypnotic snatches of the same text. This time, on a shelf in the soldier’s kitchen, Brendan finds a slim volume called Navigatio, and the men are seduced into staying. Still the journey continues, and time keeps bending: between enchanted cities and visions the pilgrims drift beneath the bridges of Ho Chi Minh City; Brendan finds himself transformed into a bored traveller in Japan’s Kansai airport.

Holland gives us St Brendan as eternal archetype. His journey is all holy. His book is itself a risky act of faith, its prose so trim and limpid that it depends for its effect on its sheer translucency. My reaction veered between admiration and ambivalence, especially in the later pages. Yet on closing the book I did feel I had experienced something true and strange.

Delia Falconer, The Australian 13 December 2014

Having had the pleasure of reading Holland’s inquiring and profound collection of travel essays Riding the Trains in Japan and experiencing the philosophical depths of his novel The Darkest Little Room, it is seems almost logical that Navigatio was born from the same mind.

Navigatio is far from a retelling of a monk’s fabled adventure. It is an original, stylistic extrapolation from a writer of great talent and passion for travel and literature, and exploring the space where those two things meet.

Joanne P, http://bookloverbookreviews.com/

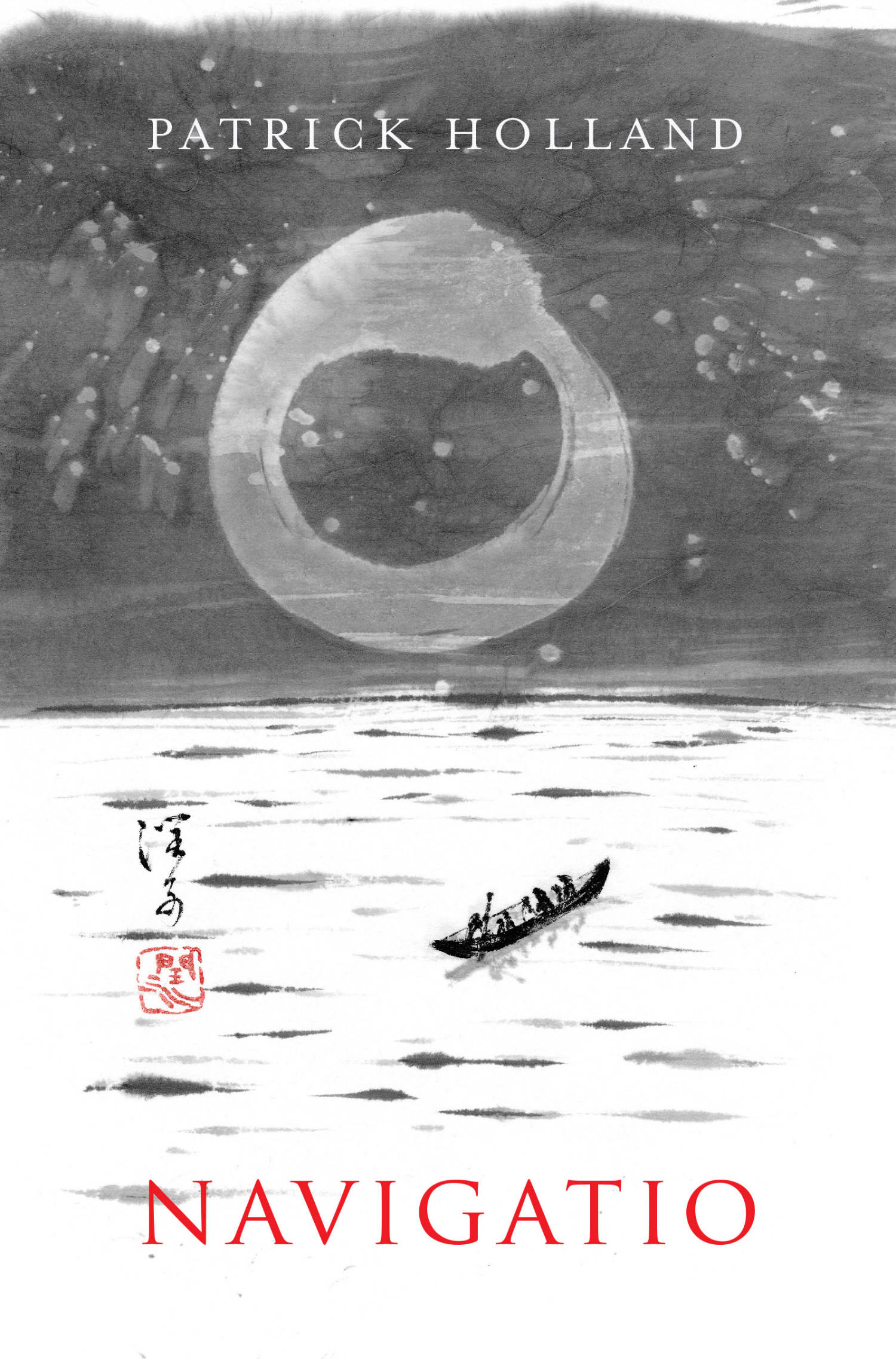

Patrick Holland’s Navigatio tells the story of Saint Brendan, a monk in early-Christian Ireland who embarks on a sea-bound pilgrimage. The religious nature of this premise offers Holland a degree of freedom from historical realism, and the oceanic regions explored by Brendan are thereby conceived as a realm of mythic and apocalyptic imagination. Brendan’s own pious heroism appears to be modelled on figures of classical mythology, as well as on the invincible heroes of Christian epic literature. The perils he faces are a fascinating blend of pagan and Christian lore, combined with a blurring of dream and reality that is facilitated through Holland’s distinctive style. The chief literary mode that Holland uses in Navigatio is that of modernism. Many of the novel’s passages might call to mind James Joyce’s Ulysses or the poetry of e. e. cummings. Yet, such devices do not appear to be pursued solely for their literary value, but rather for the visual possibilities they offer. Indeed, much of Holland’s text appears to invite the reader to consider the page as a canvas that uses language as its medium; it is clear that the book is conceived as a collaborative dialogue between literary and visual This visual element is most prominently represented in the exquisite watercolour illustrations by Junko Azukawa that encircle Holland’s narrative. These images, unmistakably drawn from the traditions of Japanese art, might be expected to produce a cultural dissonance in a novel about a sixth-century Celtic monk–mariner. Yet they act as a natural counterpoint to Holland’s own visually crafted language, and the diversity of these elements highlights the extent to which a modern literary text may be influenced by a range of cultural traditions. In this regard, Navigatio is able to exceed the sometimes mannered modernism of its literary text, and positions itself more convincingly as a work of postmodern imagination.

Christian Griffiths, Australian Book Review December 2014

Navigatio is an enchanting book. Derived from an ancient text called the Navigatio, Patrick Holland’s novella is a retelling of the legendary voyage of St Brendan of Clonfert, and it follows the form of the Irish immram: Irish immram flourished during the seventh and eighth centuries. Typically, an immram was a sea-voyage in which a hero, with a few companions, often monks, wanders from island to island, meets other-world wonders, and finally returns home. The story of Brendan’s voyage, developed during this time, shares some characteristics with immram. Like an immram, the Navigatio tells the story of Brendan, who, with some companion monks, sets out to find the terra repromissionis sanctorum, the Promised Land of the Saints or the Earthly Paradise. *chuckle* I can almost see some readers thinking, ‘um, why would I want to read that?’ Trust me, it’s gorgeous. It’s a quiet, contemplative meditation on a spiritual quest that takes a temporal form, and I loved reading it in the frantic rush up to the end of the year when work overwhelms and the pressure to do stuff for Christmas wreaks its inexorable hold on everything. Holland’s writing is sublime, and he takes you away from all that chaos into a dream world of myth where simplicity reigns. We need books like this. Books that remind us that despite the enormity and malevolence of the cosmos, there is peace to be had.

Lisa Hill, http://anzlitlovers.com