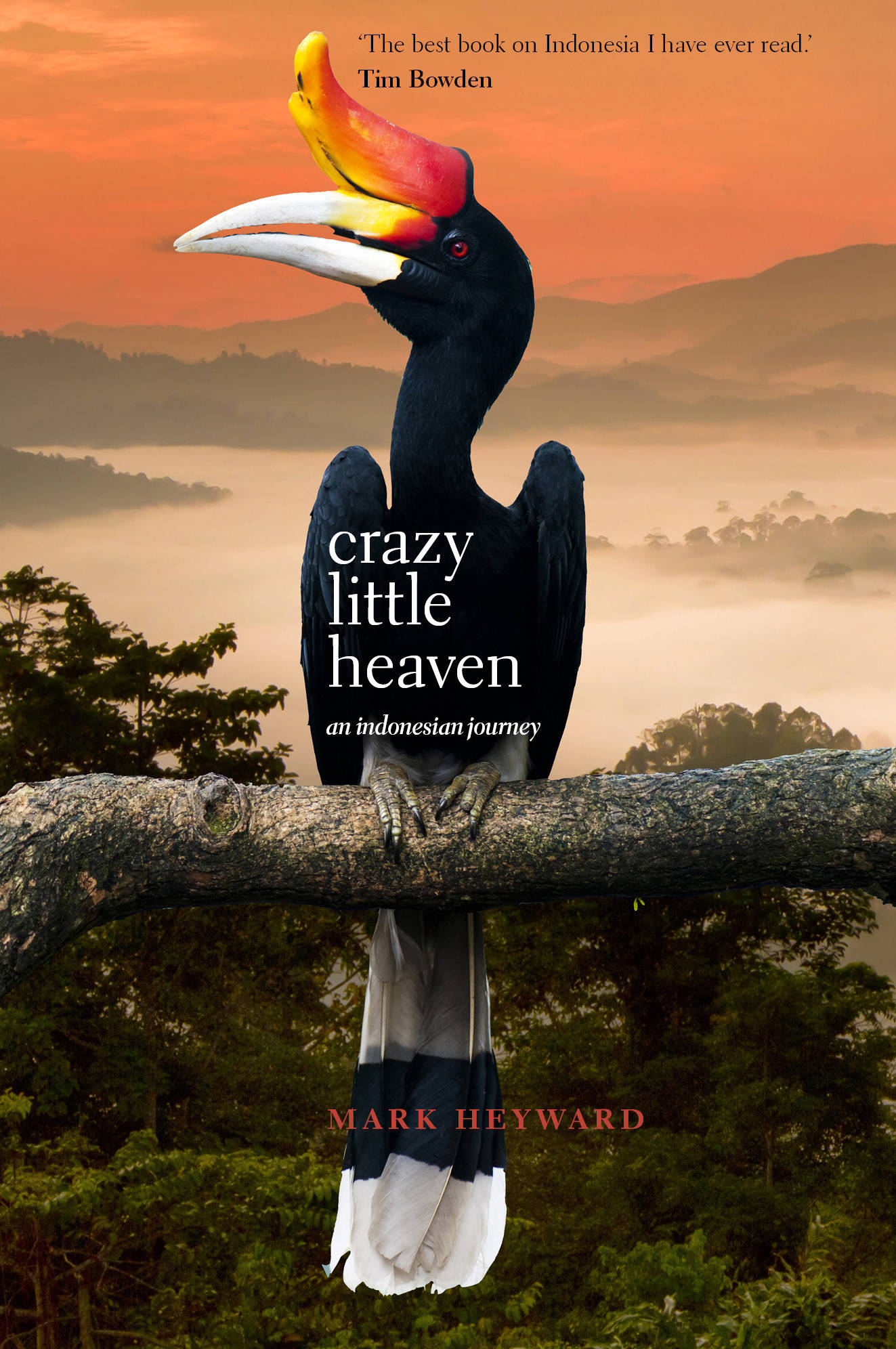

As his richly evocative book indicates, his love affair with Indonesia has evolved into a long-term commitment.

Dianne Dempsey, The Age and Sydney Morning Herald, October 5, 2013

Perhaps Mark’s journey is not so much myth-making as in placing his own in the context of the many myths westerners cannot grasp here. In order to conform to Indonesia’s marriage laws, Mark converted to Islam.

Terry Collins jakartaexpat.bix

Arduous hikes through thick jungle terrain provide Heyward ample opportunity for reflection, and he weaves in musings on the plight of Borneo’s orangutans, Indonesia’s entrenched culture of corruption, and spirituality, to name a few topics. His gentle touch ensures these detours are pleasantly idiosyncratic rather than a distraction from the overarching narrative.

Gillian Terzis The Australian 28 September 2013

Later this Anglican bishop’s son met Sopantini, a teacher from Central Java. He converted to Islam — though nicked off for a beer during the marriage ceremonies — and started a new family. He now works as an international education consultant and lives in Jakarta though has a home in Lombok.

As a travelogue the book moves well. Heyward comes across as an adaptable guy worth meeting, despite smoking kretek. He has the essentials — curiosity, sense of wonder and feel for place.

Duncan Graham, The Jakarta Post 1 January 2014

Thejakartapost.com

Heyward is a clever writer who takes sensual pleasure in the use of language. His meandering firsthand account of upriver travel is not only a tactile and intimate portrait of the beating heart of the world’s fifth-largest island, but it’s also an astute look at the rich cultural historic fabric that is Indonesia.

Bill Dalton, Tempo 15 December 2013

Heyward’s prose is evocative. Witness lines such as the following: ‘Fireflies appear above the swirling blackness of the river, their flashing points of light creating and odd counterpoint to the mid-equatorial night sky arching overhead.’ He also tries hard to create a respectful and nuanced portrait of his adopted home. Heyward concedes that he will always be a ‘foreigner’ in Indonesia, ‘but year after year I am welcomed into village, made to feel somewhere between a special guest and a kind of honorary member of the community’.

The most compelling parts of Crazy Little Heaven are those that chronicle Heyward’s adoption of the Islamic faith. The author had been raised in an Anglican household, though he had for years been uninterested in ‘spiritual life’. This changed when Heyward met his future wife who is Muslim. Heyward movingly describes committing to the teachings of Islam.

Crazy Little Heaven is a welcome addition to studies of Indonesian culture. The book is also a testament to Heyward’s skills as a wordsmith.

Jay Daniel Thompson, Australian Book Review, February 2014